Hinode 1975

Dawning of the Issei

at Nihonmachi Terrace

A photography exhibit honoring the Issei of Nihonmachi

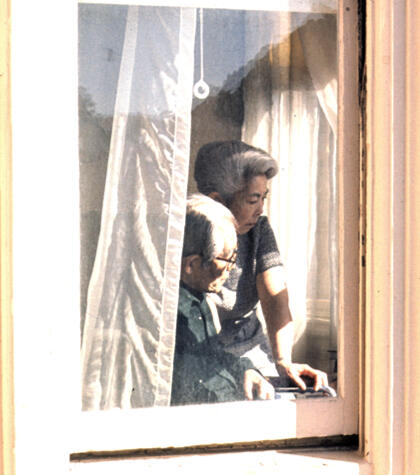

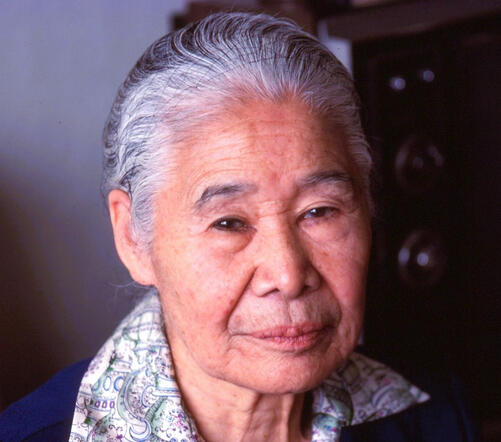

Top to Bottom: Nihonmachi Terrace today; Future home of Nihonmachi Terrace in 1940; Hikoichi & Mary Shimamoto in 1974, long time Nihonmachi Issei residents; Archbishop Nitten Ishida in 1980s, JARF's 1st President; Gary Barbaree, JARF Rep at CANE's 50th Anniversary in August, 2023

On the 50th Anniversary of Nihonmachi Terrace in 2025, this photography project reproduces a series of color slides taken in 1976 - of the first 50 residents of Hinode Tower. These photos were believed to have been lost until 2022 when they were discovered in a pile of unmarked storage boxes and returned to their rightful owner.This is an extraordinary coincidence on the eve of Nihonmachi Terrace's 50th Anniversary. For the first time ever, we will be reproducing these portraits and sharing them with the public. This exhibit will showcase 50 photographs for display, first in the lobby of Hinode Tower in late 2024 and later at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California, both in San Francisco.Nihonmachi Terrace was the first replacement housing in San Francisco’s Japanese community since the displacement of 6000 residents during the 1950 and 60s. Nihonmachi Terrace allowed these former residents to return “home.” It was a direct response by JARF - the Japanese American Religious Federation - to the loss of housing caused by redevelopment.

The Hinode Issei Photography Club, 1976

The Story Behind This Photo Project

The origin of this photo project was purely by accident when a box of old photographs was discovered in the private archives of a Berkeley historian in 2022. Realizing the importance of these images, the historian contacted Boku Kodama, the photographer, who shot these photos in 1976. Boku had been employed at Nihonmachi Terrace as its first apprentice handyman making repairs that usually accompany newly built structures.At the time, Boku was a journalist and an instructor at San Francisco State University in Asian American Studies. Being in Nihonmachi gave him the opportunity to research Japanese American history in his quest to photograph and record the community's story.Boku did not remember how he lost the photo collection other than to say that back in the day, those shooting photos in Nihonmachi shared their images freely without concerns for ownership or recognition. "We believed that sharing our work was part of our social and political duties if we wanted to see progressive changes in J-town."However, what has remained missing is the notebook Boku kept of each photograph. Over the course of these five decades, he lost this valuable information through all the moves and living situations. Thus, this project is divided into two segments: first, reproducing the photos and second, finding the names and history of each individual. "We're hoping that those who view the exhibit can give us the answers." He hopes to also review the Hinode Tower records.As a handyman, Boku was tasked with the responsibilities of repairing problems in every new unit. In doing so, he came to appreciate the personal lives of the Issei through the traditions and artifacts in their homes. Over a year's time, they came to trust him and treated him as if he was their grandson, many of whom were widows. It was then that Boku came up with the idea of photographing the Issei as part of a project he started in 1972 entitled "The Photographic History of Japanese Americans in San Francisco."During 1976 and 1977, he photographed about half of the Hinode Tower residents on Kodachrome slides. His daily work with the Issei residents also made him acutely aware of the need for social activities because so many were isolated. He was given approval by the management company to start a series of art and culture classes, partially supported by an organization he founded called the Japantown Art and Media Workshop (JAM) which provided free and low cost art classes to the community.In retrospect, Boku believes these photographs would not have been possible had he not interacted with them every day for two years. The comfort they show in these images could not have been captured by a stranger. "It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity not just because I was able to photograph them but hearing about the hard lives they endured and still, showing such kindness and love. It was a remarkable display of humanity. Because of all the immediate priorities we have today, the Issei legacy has been forgotten. What they did for us was immense but quietly told with humility, and thus, getting little bandwidth. I hope with this photo exhibit, we can start to right that wrong."

The Issei Legacy

At one time, there were 43 Japantowns in California. They were established by the first Issei when they migrated to the United States during the Meiji Period from 1868 to 1912. Being the pioneers in a new land, the obstacles the Issei faced were tougher than any generation after. They were subjected to laws against their existence, segregated mercilessly, and then placed into concentration camps with many imprisoned in actual prisons for being "enemy leaders" in their communities.Coming to America held the promise of opportunities and riches. Many had visions of working hard for a few years and returning home to live comfortably. The reality was backbreaking work, poor wages, exploitation, and racist laws.Out of necessity, Nihonmachis were established, offering a bit of home and sanctuary from surrounding hostilities. They were the social centers for both young and old, providing tradition, culture, food, faith, goods and services. Whether the Issei worked on the farms or in the cities, everyone came to the nearest Japantowns to gain the comforts of home. These communities thrived. If not for the color of their skin and the names on their storefronts, Nihonmachis were very much like any other American neighborhood.The Issei had to work harder than anyone else because the only farm lands they could use were unworkable by others. The businesses they created couldn't compete with their white counterparts so they had to set up enterprises that catered to a mainly Japanese clientele with no potential for growth except within their own community. Yet, against all these odds, the Issei persevered, succeeding and creating communities that met their needs. That is, until 1942.With the forced removal and imprisonment of all Japanese from the West Coast, by June of 1942, EVERY Japantown had become a ghost town. The huge losses destroyed the lives of many Issei.At the end of World War II, the Issei returned to San Francisco, with few options open to them. Most restarted from scratch facing a hostile society. But "home is where the heart is" so that no matter the conditions, the Issei were determined to reclaim their rightful place. Working as hard as ever, they succeeded.But a decade later, in 1955, the Issei and their adult children, the Nisei, were again pushed to the brink of disaster. Just as the first evacuation, they were unprepared for a second forced removal. This time, it would permanently destroy the community from its 25-block neighborhood to just four.It was under these circumstances that many Issei were forced out of Nihonmachi without fair compensation or alternative housing. Many had to leave the neighborhood they had lived for most of their lives.This was the conditions that sparked the religious community to get involved because it was evident the government at every level would not provide assistance. Especially hard hit were the poor and elderly.In 1970, this religious initiative became know as JARF, the Japanese American Religious Federation.

Japanese American Religious Federation

The Japanese American Religious Federation was born out of the urban renewal crisis of the 1960s when Nihonmachi was torn apart by the Redevelopment Agency. It left most residents and merchants without homes or shops in the area dictated by a callous, thoughtless plan which would later be ruled illegal and ill conceived by the San Francisco Planning Department. But for all those living through that nightmare, there was hopeless resignation.But the local churches, believing in their duty of assisting their congregations came together and launched JARF Housing, Inc. in 1970. It's Mission Statement read: "To support the charitable purposes of Japanese American Religious Federation of San Francisco, a California non-profit public charity corporation (”JARF”), including by providing housing for low income elderly or handicapped families and other low income families on a non-discriminatory basis."JARF struck a resounding cord in Nihonmachi and gathered a strong following of supporters. But due to the Redevelopment Agency's mismanagement and one track mindset of evictions without resettlement, there was an uncertainty that JARF's goal of a major low-income housing project would ever see the light of day.But through broad community support particularly from Kimochi, CANE and members of all the affiliate churches, enough funding was raised to meet RDA's criteria for the construction of Nihonmachi Terrace.In November of 1975, this first low inoome housing project in Nihonmachi opened its doors to its initial tenants. The complex included 145 units of low cost family housing and 100 units of senior housing in Hinode Tower.JARF's member churches include:

Beikoku Nichiren Buddhist Church

Buddhist Church of San Francisco

Christ Episcopal Church

Christ United Presbyterian Church

Konko Church of San Francisco

Pine United Methodist Church

Sokoji Soto Mission of San Francisco

St. Benedict Parish at St. Francis Xavier Church

S.F. Seventh-day Adventist ChurchThe property is managed by The John Stewart Company

Contact Us

We hope as many people as possible will view this exhibit to learn about the Issei generation. We also hope that descendants of those in our photos will come forward and help provide the necessary information to make this collection complete. Once the exhibit runs its course, the photos and any information compiled will be donated to one of the San Francisco archives holding Japanese American history.For more information on this photo project, please Boku Kodama via email: bokukodama@gmail.com.